Journalism is in crisis.

I am sure this is not the first time you have heard this. The past decade atleast has seen this statement become ubiquitous, especially on social media. The most visible effect of that has been legacy media publications going behind paywalls, while individual journalists and personalities branch out on their own, if they are not abandoning it completely for roles in publicity, advertising, and communication.

I compared this to the crisis in Indian cinema, which for someone like me, has been ongoing since even before the pandemic. Where are the PSAs before our films, requesting continous patronage? How much work has been done to highlight the vital role the end product of filmmaking plays in visual literacy and cultural arts? Or the employment opportunities it provides for millions across the country? Why is cinema’s crisis mode evident only now? The glamour? The huge role perceptions plays on irrational profits and losses? Your guess is as good as mine.

The comparison came up in my mind a few moments after our second Revival Cinema Project meetup had ended, and a point was made about how a large portion of the stakeholders still remain in denial about the problems facing the industry, which prevents them from coming together to discuss the possible solutions for the same.

The meetup was titled Distribution 101 and we were privileged to have two experts give us a brief overview of the film distribution system in India.

Sethumadhavan Napan has served as a distribution & marketing consultant for films, having released several indie and regional language films in multiple territories across India. He has worked on the production side as the COO of DAR Media/DAR Motion Picture and is presently involved in multiple projects across films and original series in Hindi and regional languages through two banners - Yali DreamWorks and VR Content Creators.

Laxmi Khandeshe works on the exhibition side of the film business. She closely engages with distributors across different scales of releases. From single screens to multiplex chains, her focus has been on film programming and content planning.

The two of them shared their personal knowledge and experience with us. I will be sharing brief highlights of our conversation, after an overview of the Indian distribution system.

The Theory

As per Tejaswini Ganti’s 2012 book Producing Bollywood - For the purposes of Hindi film distribution, India is divided into five major territories: Bombay; Delhi/U.P. [Uttar Pradesh]/East Punjab; C.P.[Central Province]/C.I. [Central India]/Rajasthan; Eastern; and South.

The territories are further sub-divided, (as per 2012 data), as shown in the following map.

The distributors further divide the territories as per A-, B-, and C- class centres, on the basis of the revenue earning potential. An A-class centres is a large city or town which has more cinemas and thus generates the most revenue for a distributor.

According to the book, there have been three main revenue sharing arrangements between a distributor and a producer- the Minimum Guarantee, Commission, and outright sale, which even as per Ganti’s book, was increasingly rare even in the mid-2000s and early 2010s. In the most prevalent minimum guarantee system, the distributor bids for and guarantees the producer a specific sum that is given in instalments from the onset of production. Distributors typically pay 30-40 percent of the contracted amount to the film’s producer during production, and the rest at the time of the delivery of prints. The distributors pay for the print and publicity costs as well as theater rental at the time of the film’s release. Once distributor covers the costs such as rights, prints, publicity, theater rental, as well as, extracts his 25 percent commission, any remaining box- office revenue, referred to as ‘overflow’, is split equally with the producer. This arrangement sees the distributor taking on the most amount of risk, as the producer has a certain price guaranteed for the film’s rights.

In a commission basis, a distributor bears the least amount of risk as their investments are limited to the publicity and print costs. They will deduct a certain percentage of box- office receipts as a commission and remit the rest to the producer. In the rare and archaic outright sale practice, a distributor purchases the complete distribution rights for a film for a given period of time, during which all the expenses borne and income earned belongs to the distributor.

Respondents also indicated that, out of the 1,100 single-screen theatres in the country for Hindi, only 254 generated revenue.

- Competition Commission Of India Study, 2022.

The historical context for the distribution system in India will now be complemented by the highlights from our discussion of 7th June.

A note: To ensure uniformity going forward, the salient points of the discussion will be stated while specific names and details will be withheld, as per the Chatham House Rules. In a few instances, quotes maybe attributed or it will be clarified whether a guest had stated a point or one of the listeners.

Snippets from Distribution 101

In light of the very different circumstances of 2025, where there has been massive integration, consolidation, and corporatisation of the system, the discussion began with a simple question- who exactly is a distributor and an exhibitor? In simple terms, a distributor is the one who takes on the rights to ensure that a film is distributed in a specific region and he/she creates a release strategy for the film. An exhibitor is one who owns a private theatre or chain of theatres, which will ultimately show the film, handling the programming and upkeep of the venues.

As stated, these definitions are now complicated by the fact that several organisations now undertake multiple duties. For example, Yash Raj Films is a distributor of films, in addition to being a production house and a studio. Similarly, PVR-Inox Pictures is the film distribution arm of the country’s largest multiplex chain. The integrations are done for greater control over the programming and profit shares.

A keypoint which emerged that despite the seeming formalism entering the system, a lot of the agreements and connections rely on personal and past relationships between the exhibitors, distributors, and producers.

“Malhotra- saab, last year I had to bear so many losses and the market is tight nowadays, but our relationship goes back for many years which is why I have come to you today. Otherwise, distributors do not even want to offer an MG anymore and would rather distribute the film on a commission basis,” counters Agrawal - A conversation between a distributor (Agrawal) and a Producer of a film at the Muhurat in 2005. Taken from Producing Bollywood (2012).

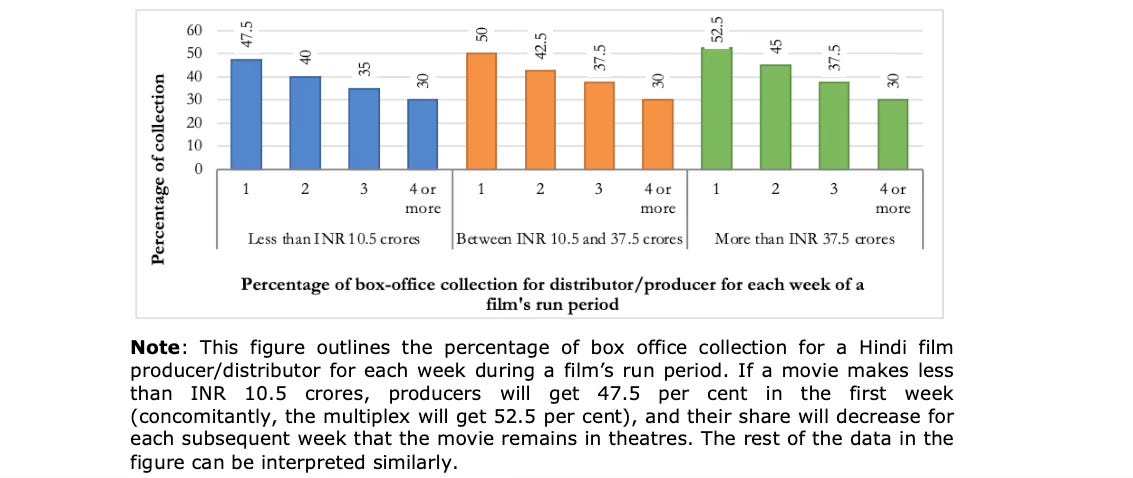

While the revenue models in the previous section still persist in some form or the other, one of the most notable aspects is the Sliding Scale model where a fixed percentage of the box office collection is shared between the exhibitor and distributor. The revenue share percentage keeps declining as the weeks of showcase increase. As an example, from having 50% in week 1, the same goes to getting 30% in week 5. This is arrived at after the distributor has a commission based agreement with the producer, with a typical rate of 6%.

“MARKET STUDY ON THE FILM DISTRIBUTION CHAIN IN INDIA” by the Competition Commission Of India featured the following chart.

The respondents to their survey stated the following: “arrangements presume that the largest audience for a film only comes in the first week. The stakeholders highlighted that word-of-mouth for regional language or niche films builds slowly. Thus, such films may have a much larger audience in its second or third week than its first week of release.”

An important factor, as evidenced even by a cursory glance at the weekly releases and trends is that films have a much shorter shelf life in theatres. The cinema managers at specific venues are quick to make programming decisions on the basis of daily film occupancy. In such scenarios, even big ticket releases or those backed by big names cannot escape the consequences of poor occupancy. While personal relationships and certain trade-off deals between the distributor/producer and exhibitor may prove to be exceptions, the on ground demand remains the sole deciding factor for the ultimate fate of a film.

While block booking in mainstream films, especially Hindi films, where the producers or their financial partners book a large number of seats to give the appearance of a good opening day/weekend has been widely reported, it’s noteworthy that even small, independent films which are releasing on a much smaller scale are now expected to ensure that they guarantee the theatres a minimum amount of sales, if the show is to be listed for a weekend or beyond.

Independent films and backers will naturally find the present environment hostile for their films, especially if not populated with high profile names in front and behind the camera. However, opportunities to garner publicity for the film, such as film festival screenings, must still be sought. There remain plenty of avenues for smaller distribution deals, with established distributors, who still deal on a personal, relationship basis. The model of block booking shows for a weekend may not be conducive for all but does offer an opportunity for general audiences to discover lesser known genres and films. Ultimately, even exhibitors will need to be patient and vigilant, to allow for a natural and long drawn out organic growth for such films.

A new trend observed has been the entry of tech/digital players in theatrical market, albeit at a smaller scale- be that from Amazon Studios or a Jio Hotstar for a couple of films. It remains too early to say on how these players, who are more established on streaming, plan their theatrical strategy for a longer term.

The demise of the so-called “multiplex films” was touched upon as well as the passing trend of recent re-releases. Sethumadhavan Napan’s personal analysis noted that with the exception of Tummbad, most releases that had a great re-run on Hindi box office were romantic musicals like Laila Majnu, Sanam Teri Kasam, Kal Ho Na Ho, Rehna Hai Tere Dil Main. It would be interesting if this heralds the comeback of the genre in a big way or whether contemporary filmmakers copy similar styles of these decade/s old films.

Lastly, the present state of the industry was tied to our own personal choices. An anecdote highlighted how even someone who works in the film industry seems to have stopped going to the theatres. While the issues of the present theatrical setup, especially high ticket prices, do remain, if those who claim to love cinema and the big screen do not invest their time and efforts to be regular at the theatre, the general audiences cannot be singled out for doing the same.

These are a few of the noteworthy points from our passionate and long discussion on that rainy Saturday afternoon. I want to thank all those who came for the sold out discussion, and especially our experts- Laxmi and Sethumadhavan. If you have anymore questions or queries regarding this topic, feel free to reach out on revivalcinemaproject@gmail.com. I will try my best to get them answered.

If you want the complete Revival Cinema Forum experience, ensure you sign up and come for the next session. The abstract cannot be translated into words.

Wishing you a good month at the movies.