Hello

You are receiving this email because either in December or January you took some time out to fill up a Google Form, answering questions on the state of Indian cinema. Firstly, I want to offer my sincere gratitude for being a part of this exercise. The various responses offered a wide range of thoughts and experiences, enriching the project’s purpose.

I think at first I should introduce myself. My name is Devang Pathak. I am a helpless cinephile, who professionally moonlights as a screenwriter and researcher. I am also one of the folks behind Mumbai Subtitles Database on X and Instagram.

Revival’s birth was a culmination of various months of uneasiness which didn’t go away even after I created the form. Friends, acquaintances, and strangers kept asking me in different ways- “So, what’s this…exactly?”. I took many defensive turns, vivid explanations, and various anecdotes to avoid saying the truth - I don’t know.

Revival Cinema Project, as it exists right now, in this newsletter and that simple form, is simply a seed, waiting to come alive, informed by the values, energy, and dedication of a community. The one thing I am decidedly sure of - it must exist tangibly in the physical world. To that end, I will soon be sharing details of our first official meetup in Mumbai. (For those in other cities who would be interested in volunteering with us to organise similar offline meetings, please do reach out on revivalcinemaproject@gmail.com).

But I don’t wish to use this newsletter to simply introduce the initiative. I think it’s vital to acknowledge my state of mind in the past month - a mix of impotence and anger.

I cannot say for certain if these feelings existed for far longer, but the passing away of filmmaker Shyam Benegal certainly brought them to the surface. I am not qualified enough to add anything substantial to the wonderful tributes and obituaries which have been offered about him over the past month. (If you still haven’t seen it, I highly recommend his interview with Samdish Bhatia.)

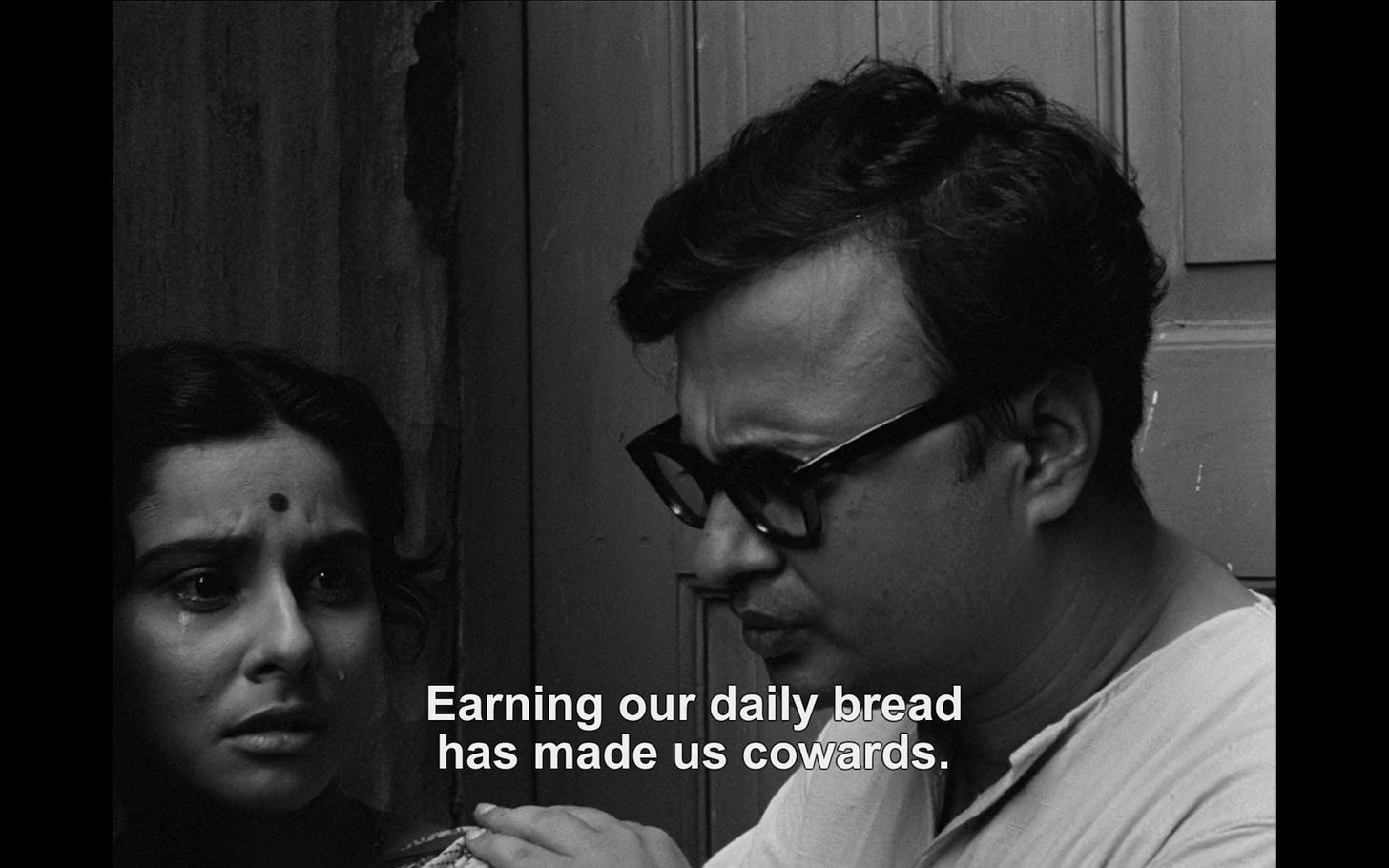

The honesty and humility that defined Benegal’s presence and the brilliance of his realistic films stands at odds with the pomp and arrogance that guides most of Indian cinema. The alarming shrinking that I have seen of cinema’s cultural relevance over the past few years had to be contrasted with the business as usual affairs of friendly interviews, roundtables, and relentlessness of celebrity worship and scandal culture. The worst aspect of such a disingenuous business and culture is that it forces one to be complicit.

The film industry doesn’t just require those in front of the camera to act. Directors, producers, writers, technicians, assistants, journalists, film critics, distributors, and even exhibitors to an extent must deal in some level of fakery with others and even at times, with themselves. I have taken part in this subterfuge multiple times, across screenings, parties, social gatherings, and even professional meetings, sometimes out of personal insecurity but also as a mode of self-preservation in an unsafe environment. If everyone around you is skilled at pretending and never showing their cards, honesty appears akin to a crime. Everything is “interesting”, “going well”, and “being developed”.

The film industry is full of people who fear they might not have a job next week, and that plays havoc with their sense of proportion. They all turn up at Cannes in the sweetness of May, lovesick for their own product, but altering where they alteration find, and many go home with a very different feeling about the stuff they brought over. One film company's success is another one's failure; somebody doing well in one quarter means that somebody must get fired in another. It's a horrible world really, packed with fear and lying and delirium. - Andrew O’ Hagan, “Two Years In The Dark”, Granta Film Issue, 2004

I know how naive I must appear to some of you. Jean-Luc Godard had already declared decades back- “Cinema is the most beautiful fraud in the world.” The very essence of cinematic or rather any storytelling is the untruth, one may argue. However, does that necessarily dictate that the systems which support it must also rely on manipulation, distraction, and instability? I remain unconvinced.

The five years I have spent in and around this industry have left me in a state similar to that of Govind Nihalani’s Anant Velankar. (The English translation of the poem can be found here.)

Alright, confession time over.

My reason behind these revelations isn’t to further propagate an atmosphere of cynicism or helplessness. I believe the context was important to highlight that these feelings and thoughts were vital for me to experience so that the need for a natural resurgence and rejuvenation could also take place.

Time is cyclical. We tend to only associate ourselves to our present reality, believing that all our joys and woes are unique. They are not. In 1919 for instance, five of the most well known individuals in Hollywood came together and made a declaration:

A new combination of motion picture stars and producers was formed yesterday, and we, the undersigned, in furtherance of the artistic welfare of the moving picture industry, believing we can better serve the great and growing industry of picture productions, have decided to unite our work into one association, and at the finish of existing contracts, which are now rapidly drawing to a close, to release our combined productions through our own organization. This new organization, to embrace the very best actors and producers in the motion picture business, is headed by the following well-known stars: Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, William S. Hart, Charlie Chaplin and D.W. Griffith productions, all of whom have proved their ability to make productions of value both artistically and financially.

We believe this is necessary to protect the exhibitor and the industry itself, thus enabling the exhibitor to book only pictures that he wishes to play and not force upon him (when he is booking films to please his audience) other program films which he does not desire, believing that as servants of the people we can thus serve the people. We also think that this step is positively and absolutely necessary to protect the great motion picture from threatening combinations and trusts that would force upon them mediocre productions and machine-made entertainment.

William S. Hart would later back out, but what the four of these individuals achieved was the birth of United Artists film production company. As the book on its history notes, “Like all manifestos, it did not always live up to its ideals”. And yet, the filmography of this production company includes some of the best films ever made.

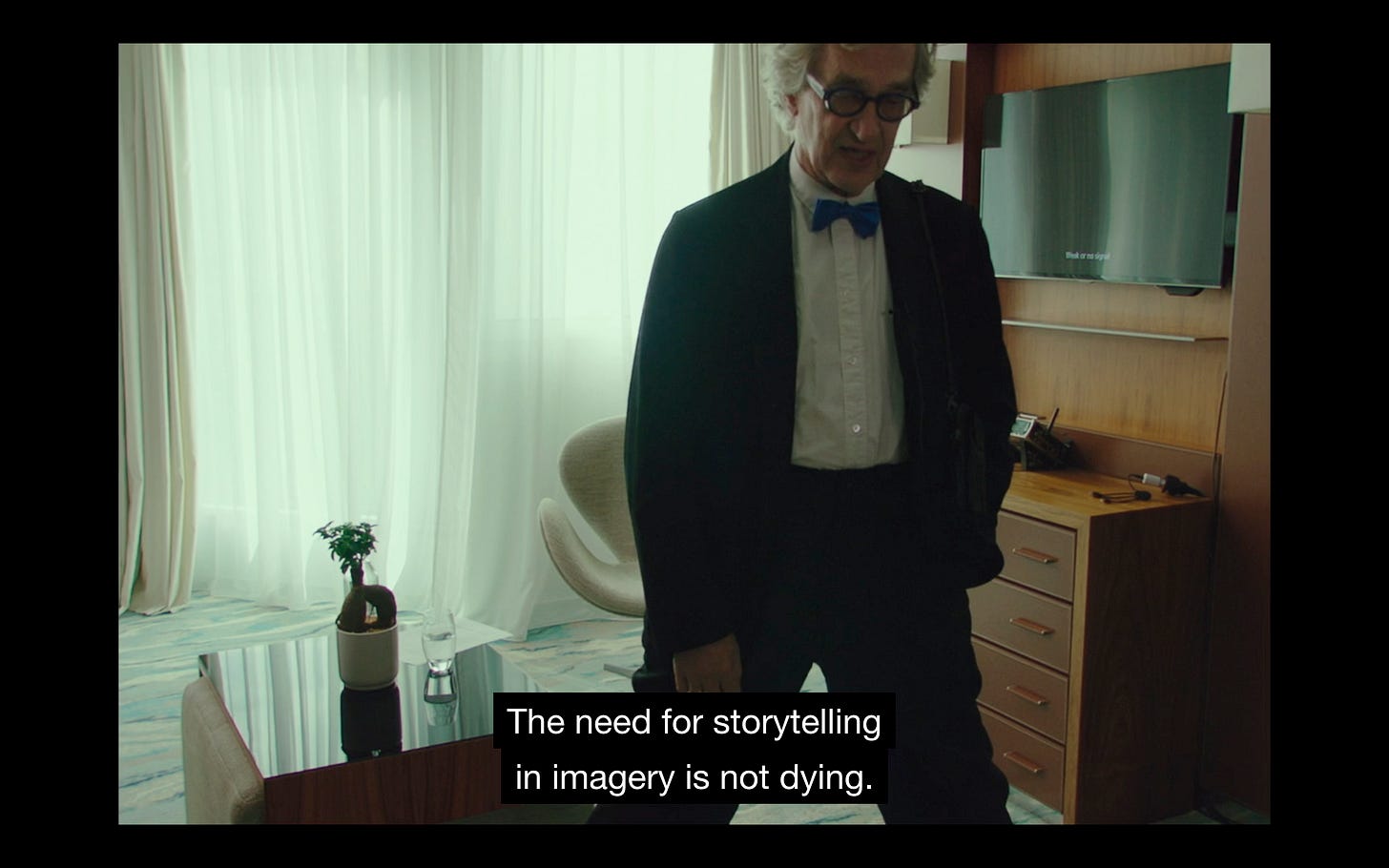

The cine-artist has always been concerned with the future of this young artform. Wim Wenders, whose visit to India next month has generated a lot of excitement among cinephiles, made Room 666 in 1982, inviting the likes of Steven Spielberg, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, and Werner Herzog to answer the question - Is cinema a language about to get lost, an art about to die? The documentary concerned itself primarily with the threat of television and home video.

Lubna Playoust carried this conversation ahead in her 2023 film Room 999, inviting scores of filmmakers from across the world to answer the same question on the future of cinema, as a tribute to Wenders’ film. I personally consider the two films extremely important to the challenges we face and urge you to seek out both Room 666 and Room 999.

Playoust’s documentary begins with Wim Wenders himself, providing his wonderful insights and hard truths in a soothing manner. Here’s what he mentioned in his opening answer:

“And let’s not forget, it was born as a fairground attraction. Even the Lumiere brothers didn’t think much of their invention. They thought it was a passing fancy and it was going to be attractive to people in fairgrounds. Little did they know.”

For me, this serves as a humbling reminder that humanity has never possessed the gift of complete foresight, no matter how hard it tries to exert control on the future.

Wim’s answer finally concludes with the following message:

“Cinema is lost. It will never be the same. Professions are dying. And what we do with the art of storytelling that is upto you, and me a little bit longer and all of you who watch this, watch this and decide if you want to be the complete victims of this digital revolution. Or if you want to keep some dignity, and remain masters of ourselves. I wish you a bright [laughing] future. All my best to future filmmakers.”

And so, I ask you at the end of this long letter - Shall we try to find the future of storytelling?

Scary? Yes. Daunting? Surely. Hopeful? Absolutely.

Thank you for reading.

Wish you a great month at the cinemas.

See you soon.

Regards,

Devang Pathak

A lovely post. Whatever shape this takes, I shall be looking forward to it! All the best!